Disclaimer: This post reflects patterns and lessons learned from building distributed ML systems at production scale across multiple environments. Technical details have been generalized, and no proprietary information from any specific organization is disclosed.

I've run Ray in production at three companies over the past three years:

- A fintech platform: Built an ML platform on AWS serving community financial institutions. Dozens of GPUs running RLHF with PPO. Distributed training, hyperparameter optimization, all of the fun stuff

- A large financial institution: Enterprise agent platform serving thousands of analysts. Worked with vLLM on Ray Serve, distributed fine-tuning, vector search across massive document collections.

- A QSR chain: Conversational AI for drive-thru ordering. Hundreds of thousands of LLM calls daily, sub-1.5-second end-to-end latency, three simultaneous inference engines orchestrated through Ray.

Each environment had completely different constraints — financial compliance vs. real-time voice latency vs. enterprise scale — but the patterns that emerged were surprisingly consistent.

And unfortunately so were the ways Ray broke.

Most Ray content falls into two buckets:

- "here's how to use

ray.remote" - Anyscale's marketing materials lol

There's almost nothing in between for the engineer who's actually trying to ship a distributed ML system and hitting walls that the documentation doesn't warn you about and reliance on LLM's for debugging goes through the roof.

Instead of organizing by Ray component (Train, Serve, Data), I wanted to walk through the real problems I faced and how Ray fit (or didn't fit) into solving them. The ugly parts are included because they're the parts that actually matter. Nobody's perfect

Table of Contents:

- The Mental Model

- The Execution Model

- Fintech RLHF Cluster

- Enterprise RAG

- Real-Time Inference

- Streaming & Ray Data

- The Evolution

- Serialization

- Resource Management

- Debugging in Production

- Antipattern Hall of Fame

- Performance Checklist

- What I'd Tell Myself

Part 1: The Mental Model

Before anything else, the single most important insight about Ray:

Ray is a distributed operating system for Python processes.

Once this clicks, everything else will follow:

- Tasks are processes

- Actors are long-lived processes with state

- The object store is shared memory across machines

- The GCS (Global Control Store) is the kernel's process table

- The Raylet is the per-node scheduler

- Ray Train orchestrates PyTorch (i see people mixing this up often, it doesn't replace it)

- Ray Serve is a deployment framework

The engineers I've seen struggle with Ray try to use it like a library. Call a function, get a result, move on.

The engineers who succeed treat it like infrastructure. You don't "use" an operating system the way you use a library; you build on top of it and respect its constraints.

Part 2: The Execution Model (expect to find buried bodies here)

GCS: The Actual Single Point of Failure

Ray markets itself as decentralized.

In practice, the Global Control Store is the brain.

Pre-Ray 2.0, it was a Redis instance on the head node. Post-2.0, it's an embedded gRPC service with optional Redis for HA.

The operational reality hasn't changed as much as you'd hope.

GCS tracks everything: actor registry, placement groups, resource availability, job metadata. If GCS goes down, your cluster enters a degraded state. Existing running tasks continue, but no new scheduling decisions can be made.

At one financial institution, we were running Ray 2.7 when a head node had a memory spike from an unrelated monitoring process.

GCS went unresponsive for ~45 seconds (treat every estimate with an assumed -ish at the end to account for my ellis grey level memory). Every in-flight actor creation call failed with gRPC UNAVAILABLE errors that, at the application layer, looked nothing like a GCS issue. The error message pointed at the downstream service, not the scheduler.

We spent two hours chasing a phantom bug in our vLLM deployment before someone checked the head node metrics.

The fix ended up being simple: retry logic that understands gRPC status codes and doesn't immediately assume the called service is broken.

Another disclaimer. I had Claude help me with generating the code snippets in this article since I can't share proprietary code. But it HAS been checked, so rest assured.

# Production-ready actor creation with retry

from tenacity import retry, stop_after_attempt, wait_exponential

@retry(stop=stop_after_attempt(5), wait=wait_exponential(multiplier=1, min=2, max=30))

def create_actor_with_retry():

try:

return MyActor.remote()

except ray.exceptions.RayActorError as e:

if "UNAVAILABLE" in str(e):

raise # Retry

raise # Don't retry other errors

The lesson: GCS fault tolerance was experimental before Ray 2.9. Even with GCS FT enabled in newer versions, that 10-30 second failover window will generate errors that look nothing like what they actually are.

This also brings about a richer lesson about the age we're moving into. Despite LLM's helping track root causes and everyone preaching "Logs are all you need", you will NOT thrive without good system design intuition. You NEED to understand what each service is responsible for and what is a Non-Goal of it.

The Ownership Model (Most Expensive Lesson)

Ray uses ownership-based distributed reference counting. THIS is what that means:

When you call ray.put(x), the calling process becomes the owner of that ObjectRef. If the owner process dies, the object becomes unreachable even if the data is still physically present in the object store on another node. OOF what a caveat.

At the fintech platform, during our early RLHF experiments, we had a driver script that orchestrated all four models (policy, reference, reward, value) in the PPO loop.

The driver launched thousands of tasks across the training run. Each return ObjectRef was owned by the driver. When the driver process OOM'd — which happened because it was holding references to intermediate results from thousands of generation steps — every single ObjectRef it owned became garbage-collectible.

Downstream tasks that depended on them started throwing ObjectLostError, which cascaded through the entire training pipeline.

We lost 18 hours of PPO training. At five figures per month in spot instance costs, that loss HURT like hell. lmao imagine explaining this to your boss.

And so, naturally (as well as structurally from the inherent pressure of losing my job), we moved to a tree reduction pattern.

So instead of the driver owning everything:

# DANGEROUS — driver owns all 100K ObjectRefs

refs = [process_batch.remote(i) for i in range(100_000)]

results = ray.get(refs) # Driver must stay alive for ALL of these

# SAFER — delegate ownership via intermediate actors

@ray.remote

def process_and_reduce(batch_ids):

refs = [process_single.remote(i) for i in batch_ids]

return aggregate.remote(refs) # Ownership stays in this actor

chunks = [list(range(i, i+1000)) for i in range(0, 100_000, 1000)]

meta_refs = [process_and_reduce.remote(chunk) for chunk in chunks]

The Ray docs mention ownership, but they don't convey the gravity of what happens in a long-running training job when the owner process dies. Reading the docs gave me a 2/10 understanding. Losing compute gave me a 10/10 understanding :))))))

Object Store: Shared Memory With Sharp Edges

Ray's object store uses shared memory via /dev/shm. Objects are stored as memory-mapped files. This is actually really elegant — to non-nerds who actually have lives, this means zero-copy reads on the same node and Arrow IPC across nodes. Fun fact, i learned about Arrow at this point in my career, how embarrassing (despite using Parquet and Apache based frameworks for forever-oclock).

The sharp edge i'm talking about here is this: on Linux, /dev/shm defaults to 50% of RAM.

In Docker without --shm-size, you get 64MB.

Your Ray workers will crash with SIGBUS errors when the object store fills up, and the error message will not tell you it's a shared memory issue.

I hit this exact failure more than three mutherfreaking times — basically once at each company.

At the QSR chain, it happened during our initial GKE deployment because the Kubernetes pod spec didn't include the emptyDir volume mount for /dev/shm. The error looked like a segfault in the inference engine. We spent a full afternoon on it WOOP WOOP LOVE THE JOB BABYYYYY

# In Kubernetes: ALWAYS DO THIS

volumes:

- name: dshm

emptyDir:

medium: Memory

sizeLimit: 16Gi

Configure object spilling to fast storage pls, not the default /tmp:

ray.init(

_system_config={

"object_spilling_config": json.dumps({

"type": "filesystem",

"params": {

"directory_path": ["/mnt/nvme0/ray_spill"]

}

}),

"min_spilling_size": 100 * 1024 * 1024, # Don't spill objects < 100MB

}

)

On cloud instances with NVMe drives, spilling is pretty fast.

On EBS or network storage, it's catastrophic for latency.

At one enterprise environment we were on EBS volumes initially and spilling added 200-500ms per object restoration.

Switching to local NVMe brought that down to 5-10ms.

Sometimes i feel like the huberman of optimization, we love that.

Part 3: Fintech RLHF Cluster (Dozens of GPUs)

The Problem

The fintech platform served community financial institutions. These banks were losing customers to neobanks that offered "smart" features.

We needed to give them ML-powered capabilities like fraud detection, credit risk, transaction categorization, all without each bank building its own ML team.

The mandate expanded from traditional ML to LLMs and post-training. We were building an RLHF pipeline with PPO before most people had even heard of RLHF.

The target: train domain-specific models (3B-7B parameters) that understood financial services.

The Architecture

RLHF with PPO requires four models running simultaneously:

Stage 1: Policy Model (multiple GPUs) — generates responses Stage 2: Reference Model (frozen) — computes KL divergence Stage 3: Reward Model — scores generated responses Stage 4: Value Model — estimates advantage function

Each stage has completely different compute characteristics: - The policy model needs the most GPUs because it's doing both forward and backward passes - The reference model is frozen (inference only), so it needs less memory - The reward model is smaller - The value model trains alongside the policy

Total: dozens of V100 GPUs, orchestrated through Ray

Napkin Math

Here's the intuitive math that shaped every decision:

Used Claude to source the cost as of February 2026

Dozens of V100 GPUs (im basing this off of p3.2xlarge instances on AWS):

├── On-demand: ~$3/hr per GPU

├── Spot: ~$0.90/hr per GPU

├── Reserved (1yr): ~$2/hr per GPU

One full RLHF run (SFT + RM + PPO + Eval):

├── Thousands of GPU-hours

├── At reserved pricing: five figures per run

└── 3-5 runs per experiment: mid-five figures per experiment cycle

HPO with Optuna/Ray Tune:

├── 20 trials × partial PPO runs

├── Tens of thousands of GPU-hours per sweep

└── Monthly total: five figures in GPU spend

At five figures monthly, every architectural decision was a cost decision.

Placement Group Challenges

The policy and value models needed to communicate frequently (advantage estimation requires coordinating between them every training step). You want them close together — ideally same node — for fast inter-process communication.

But V100s only have 16GB of HBM2. You can't fit both models on the same node with enough headroom.

My placement group journey:

# Attempt 1: STRICT_PACK — fails, not enough memory per node

pg = placement_group([{"GPU": 4}], strategy="STRICT_PACK") # OOM

# Attempt 2: STRICT_SPREAD — works but allreduce is 10x slower cross-node

pg = placement_group([{"GPU": 1}] * 4, strategy="STRICT_SPREAD")

# Attempt 3 (after weeks of profiling): PACK with 2 GPUs per bundle

pg = placement_group(

[{"GPU": 2}, {"GPU": 2}],

strategy="PACK",

)

# Policy+Value on 2-GPU node, Reward+Reference on another

Getting to Attempt 3 took weeks. The frustration wasn't just the Ray API — it's that placement groups interact badly with autoscaling. When you request a STRICT_PACK group that requires 4 GPUs but no single node has 4 free, the group enters PENDING. The autoscaler sees pending placement groups and tries to add nodes — but it doesn't know you need a single node with 4 GPUs. It might add 4 single-GPU nodes, which doesn't help.

We eventually landed on requesting placement groups with a timeout and always having a fallback:

pg = placement_group(

[{"GPU": 2, "CPU": 8}],

strategy="STRICT_PACK",

lifetime="detached",

)

try:

ray.get(pg.ready(), timeout=300) # 5 min max

except ray.exceptions.GetTimeoutError:

remove_placement_group(pg)

raise RuntimeError("Could not place model — check GPU availability")

The Spot Instance Problem

To bring the GPU bill down, we configured the autoscaler for spot instances. This worked beautifully for our CPU workers (data preprocessing, evaluation).

GPU training was a bit different though.

When a spot instance gets reclaimed mid-PPO-training:

- The Ray worker on that node dies

- NCCL communicators break (NCCL comms are not resizable after creation)

- ALL workers must restart the NCCL group

- Everyone loads from the last checkpoint

- Training resumes

The problem is that we were checkpointing every 30 minutes to save time. A spot interruption meant losing up to 30 minutes of PPO training across the entire cluster.

The fix took ~three months of iteration:

- Aggressive checkpointing: every 100 PPO steps instead of every epoch

- Custom Ray Train failure handler that detected AWS's 2-minute spot interruption warning via instance metadata

- "Warm spare" pattern: idle GPU workers pre-loaded the model so failover was faster

- Critically: checkpoints to S3, never local disk. When a node dies, local checkpoints die with it.

I can't emphasize the checkpoint-to-shared-storage point enough. This is the #1 Ray Train mistake I've seen in every environment. Save to S3 or NFS. Never local disk. The documentation mentions this but doesn't scream it loudly enough.

The Optuna Integration That Haunted Us

Ray Tune's Optuna integration (OptunaSearch) had subtle bugs around trial pruning. When Optuna's MedianPruner decided to prune a trial, the corresponding Ray Tune trial didn't clean up its GPU resources immediately. The actor would linger for 30-60 seconds before garbage collection caught it.

During HPO sweeps with 20 concurrent trials, this meant 2-3 GPUs were perpetually "leaked" to zombie trials. On a cluster costing five figures monthly, that was thousands of dollars per month in wasted compute.

# The workaround: explicit cleanup in every trial

def train_fn(config):

try:

for step in range(1000):

loss = train_step(config)

tune.report(loss=loss, step=step)

finally:

# Force GPU memory release even on pruning

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

gc.collect()

if dist.is_initialized():

dist.destroy_process_group()

The DPO Pivot

DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) emerged as a simpler alternative to PPO.

The team debated switching for months.

DPO doesn't need a separate reward model or value model. It directly optimizes the policy using preference data. That would've reduced our GPU requirement from dozens to around a dozen.

The monthly bill would drop significantly.

But DPO has a fundamental limitation: it's an offline algorithm. It learns from static preference data.

PPO is online — it generates new data during training.

For financial models where the distribution shifts constantly (new fraud patterns, new transaction types), PPO's online nature ended up being more robust.

The compromise we landed on: DPO for initial alignment (cheaper, faster iteration), PPO for final production training (better out-of-distribution robustness).

This hybrid approach cut costs by roughly 40% while maintaining quality.

This ended up being probably the highest-leverage decision we made on the entire platform. Not a Ray decision per se, but Ray's flexibility to support both paradigms (DPO via standard TorchTrainer, PPO via the full 4-model actor setup) made the hybrid approach feasible without rebuilding the infrastructure.

Part 4: Enterprise RAG and Network Challenges

The Problem

At a large enterprise, thousands of analysts were spending hours on repetitive research: finding documents, summarizing reports, pulling data from internal systems.

The agent platform needed sub-100ms retrieval across massive document collections and an agent layer that could orchestrate multi-step workflows.

Where Ray Fit

Ray wore two hats:

- Ray Train for distributed fine-tuning of our internal models

- Ray Serve wrapping vLLM for multi-model inference

The serving architecture:

vLLM on Ray Serve:

├── Head node: m5.4xlarge (scheduler, dashboard, metrics)

├── GPU workers: multiple nodes with A10G GPUs

├── Primary: 70B model (4-bit quantization, tensor parallel across 4 GPUs)

│ └── 2 replicas for HA

├── Secondary: 13B model (fp16, single GPU, 4 replicas)

└── Routing: lightweight classifier sends simple queries to 13B

The autoscaling config that worked:

@serve.deployment(

max_ongoing_requests=256,

autoscaling_config={

"min_replicas": 2,

"max_replicas": 8,

"target_ongoing_requests": 128, # 50% of max — this is key

"downscale_delay_s": 600, # 10 min — GPUs are expensive to restart

},

)

The mistake i made initially: setting target_ongoing_requests equal to max_ongoing_requests.

If your scaling target equals your hard cap, then by the time autoscaling triggers, your replicas are already at capacity and requests are queuing.

Set the target to 50-70% of max. This gives the autoscaler headroom to react before users feel the pain.

The Network That Ate Our Latency

Enterprise network security policies required all traffic between subnets to go through network firewalls with deep packet inspection.

Ray's inter-node communication (gRPC for control plane, custom protocol for object transfers) was being inspected by DPI appliances.

The result: 5-15ms added latency per RPC.

For basic task scheduling, you barely notice.

For vLLM tensor parallelism across nodes — where allreduce operations happen thousands of times per second — this ended up being catastrophic. Operations that should take 2ms were taking 20ms.

Our 70B model was running 10x slower than benchmarks predicted. OOF.

We worked with the network team to create a dedicated "ML subnet" with relaxed DPI rules.

This sentence describes 6 weeks of security reviews, architecture board approvals, risk assessments, and explaining what NCCL is to people who very reasonably didn't know what NCCL is.

A job description of enterprise REALLY should be ability to sit patiently through red tape.

In the meantime, we limited tensor parallelism to within a single node (4 GPUs max). This constrained our maximum model size but kept latency acceptable. The practical impact: our 70B model had to use 4-bit quantization to fit in 4×24GB A10G GPUs.

Not ideal, but the quantized model at fast latency beat the full-precision model at 10x the latency.

If you're building Ray clusters in a large enterprise: Budget 6-8 weeks for network configuration alone. Your network team isn't trying to make your life difficult — they're enforcing policies that exist for good reasons. Come to the table with a clear diagram of what ports Ray needs, what protocols it uses, and what the traffic patterns look like.

The LangChain Tax

We initially built the agent layer with LangChain's memory systems.

Profiling revealed that LangChain's abstractions were responsible for 60% of the latency in agent responses.

The default memory implementations use generic ORM-layer abstractions that add unnecessary round trips and overhead.

# After optimization: <1ms per retrieval

# Direct SQLAlchemy Core with prepared statements

async def get_memory(session: AsyncSession, session_id: str):

result = await session.execute(

text("""

SELECT role, content, created_at

FROM conversation_memory

WHERE session_id = :sid

ORDER BY created_at DESC

LIMIT 10

"""),

{"sid": session_id}

)

return result.fetchall()

Stripping LangChain's memory abstractions and going direct-to-database cut agent response time from ~8s to ~3s.

The lesson: when your inference chain is Ray Serve → vLLM → LangChain → database → response, the bottleneck is often NOT where you expect.

Profile everything. Trust nothing.

The Evaluation Speedup That Actually Mattered

One Ray pattern that paid for itself immediately: parallelizing the evaluation harness.

Agent evaluation is fundamentally harder than traditional ML eval.

A fraud model has precision/recall/F1.

An agent that researches companies and writes reports has... "quality"?

We settled on five dimensions: factual accuracy, source attribution, reasoning validity, safety compliance, and completeness. Each evaluation required an LLM-as-judge call.

1000 test cases × 5 dimensions = 5000 evaluation calls

Each LLM-as-judge call: ~2s

Sequential: 5000 × 2s = 10,000s = 2.8 hours

Parallel with Ray (50 concurrent tasks): ~3.3 minutes

That 50x speedup was the difference between "eval after every code change" and "eval once a week and make dua."

This is one of those cases where Ray's task model — just @ray.remote on the eval function, fan out, collect results — is exactly what you want. Simple, effective, no orchestration overhead.

Part 5: Real-Time Inference at the Edge of Chaos

The Constraint: Human Conversation Dynamics

Drive-thru AI has a hard latency budget dictated by human perception.

More than ~2 seconds of dead air and the customer thinks the system is broken:

Customer speaks → ASR → LLM → TTS → Speaker

├── ASR (speech-to-text): 200-500ms

├── LLM inference: 300-800ms ← what we're optimizing

├── TTS (text-to-speech): 100-300ms

├── Network + audio I/O: 100-200ms

├── Total budget: < 1500ms end-to-end

300-800ms for LLM inference.

That's the window.

And we had hundreds of thousands of calls daily across hundreds of restaurants.

Three Engines, One Router

This is the architectural decision i'm most proud of, and also the one that caused the most operational headaches.

Most companies pick one inference engine.

We ran vLLM, TensorRT-LLM, AND SGLang simultaneously behind a Ray Serve router.

(yes this was probably insane in retrospect but it WORKED lol)

| Dimension | vLLM | TensorRT-LLM | SGLang |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latency (TTFT) | Medium (~15ms) | Best (~8ms) | Good (~12ms) |

| Throughput | Good | Best (CUDA graphs) | Good |

| Flexibility | Best (any model) | Poor (requires compilation) | Good |

| Prefix caching | Basic | No | Best (RadixAttention) |

| Model swap time | Seconds | Minutes | Seconds |

The routing logic:

IF peak_hour AND latency_critical:

→ TensorRT-LLM (lowest latency, pre-compiled)

ELIF shared_system_prompt:

→ SGLang (RadixAttention caches the shared prefix)

ELIF new_model_deployed:

→ vLLM (most flexible, no compilation step)

ELSE:

→ cheapest_available by current GPU utilization

The SGLang Insight

Every drive-thru conversation starts with the same system prompt — the restaurant's menu, hours, promotions, instructions. That's 2,000-4,000 tokens. With hundreds of restaurants each having ~20 concurrent sessions at peak:

Traditional inference:

Thousands of sessions × 3,000 token prefix = millions of tokens of redundant prefill

SGLang with RadixAttention:

Prefix computed ONCE, cached in radix tree.

Each new session prefills only their unique tokens (~50-100).

Result: ~60-80% reduction in first-token latency for ongoing conversations.

This was the difference between hitting our 800ms LLM latency target and not.

Without prefix caching, we needed roughly 3x the GPUs to meet the same latency SLA.

The Router's Shadow Queue Problem

Running three engines means three separate batching systems with different optimal batch sizes.

The model router had to understand each engine's internal queue state.

But the engines expose different metrics:

- vLLM:

num_running_requestsandnum_waiting_requests(useful) - TensorRT-LLM: throughput metrics but not queue depth (less useful)

- SGLang: cache hit rate (very useful) but different queue semantics

We ended up maintaining our own shadow queue model in the router, which tracked estimated queue depth based on observed latencies and request rates.

This worked 95% of the time.

The other 5%, when our model diverged from reality — usually during traffic spikes — we'd get brief latency spikes as the router sent requests to an engine that was already saturated.

In practice, a simple exponential moving average of response latency per engine, updated every second, ended up being good enough.

Napkin Math: Why It Worked

Hundreds of thousands of LLM calls/day ÷ hundreds of restaurants

Peak hours (lunch + dinner, 4 hrs): hundreds of calls/hr/restaurant

Peak concurrent: tens of calls/second

A 13B model on a single A100: ~25K output tokens/sec

Need: 100K tokens/sec / 25K = 4 GPUs minimum

Reality: 8-16 A100s with burst headroom

Monthly GPU cost: five figures

Per restaurant: hundreds monthly

One part-time drive-thru employee: ~$1,500/month

Even at 50% automation: ROI is massive

Tensor/Pipeline Parallelism Boundaries

For a 70B+ model across multiple GPUs, you have two parallelism options:

- Tensor parallelism: Split individual layers across GPUs. Requires NVLink/NVSwitch for fast communication. Works beautifully within a single node (4-8 GPUs on NVLink, microsecond latency between them).

- Pipeline parallelism: Split sequential layers across nodes. Tolerates higher latency but has "bubble" inefficiency (GPUs idle while waiting for earlier stages to complete).

The right answer ended up being obvious: tensor parallelism within a node, pipeline parallelism across nodes.

But Ray's placement groups don't natively understand GPU topology. They see all GPUs as equivalent.

A placement group with {"GPU": 4} might give you 4 GPUs on the same node, but it doesn't guarantee they're NVLink-connected vs. PCIe.

On GKE, that distinction matters — NVLink gives you ~600 GB/s, PCIe gives you ~32 GB/s.

That's a 19x difference. what the helly.

We used custom resources marking NVLink topology:

# Node 1 (4x A100, NVLink-connected):

ray start --resources='{"GPU": 4, "nvlink_group_0": 4}'

# Node 2 (4x A100, NVLink-connected):

ray start --resources='{"GPU": 4, "nvlink_group_1": 4}'

# Tensor parallel within NVLink group

tp_group_0 = placement_group(

[{"nvlink_group_0": 4}], strategy="STRICT_PACK"

)

We noticed that our tensor-parallel 70B model was running 5x slower than expected on a "4-GPU node."

Turns out the GPUs weren't NVLink-connected — the GKE node pool had mixed topology.

Custom resources solved it, but debugging that was a fun afternoon.

Async Actors and Health Check Cascades

One pattern that i haven't seen written up anywhere: concurrency groups for health checks.

When you deploy an inference engine behind Ray Serve, your load balancer needs health checks. By default, all method calls share the same concurrency pool.

Health checks compete with inference for concurrency slots.

During peak traffic, all slots were occupied by inference requests.

Health checks couldn't get through.

The load balancer saw the replica as "unhealthy" and pulled it from rotation.

Remaining replicas got even more traffic, their health checks also failed, and we cascaded into a full outage.

All because the health check couldn't get a slot. lmao what a way to discover THAT.

Concurrency groups fix this:

@ray.remote

class InferenceServer:

def __init__(self):

self.model = load_model()

@ray.method(concurrency_group="health")

async def health_check(self):

return {"status": "ok", "gpu_memory": get_gpu_memory()}

@ray.method(concurrency_group="inference")

async def predict(self, input_data):

return self.model(input_data)

server = InferenceServer.options(

concurrency_groups={"health": 10, "inference": 8},

).remote()

Health checks get their own pool, completely independent of inference. They always respond, even under saturation. This pattern should be in every Ray Serve deployment.

KubeRay Operational Reality

At multiple environments, we ran Ray on Kubernetes via KubeRay. Hard-won operational learnings:

The autoscaler conflict:

KubeRay's operator and Ray's built-in autoscaler are separate systems that can fight each other. KubeRay watches Kubernetes resource requests; Ray's autoscaler watches Ray's internal demand signal.

If both are active, they scale independently and create oscillation. Pick one.

At one company, we used KubeRay for node lifecycle and disabled Ray's autoscaler. At another, the opposite — Ray's autoscaler with KubeRay in a minimal "cluster provisioner" role.

Ghost nodes:

When Kubernetes restarts a pod (OOM kill, health check failure, node drain), the pod gets a new IP. Ray doesn't automatically deregister the old node.

You get "ghost nodes" — entries in the GCS that point to dead processes, consuming logical resources in the scheduler. We wrote a sidecar container that periodically reconciled Ray's node list with Kubernetes' pod list.

Newer KubeRay versions handle this better, but it was a real problem.

Head node CPU = 0: Always set num-cpus: '0' on the head node. The head node should NEVER run user tasks — its job is GCS, dashboard, autoscaler. If tasks land there and cause load, your entire cluster's scheduling degrades.

GCP Pain Points

Ray on GCP (GKE) has noticeably worse ergonomics than on AWS (EKS).

A few specific issues we hit:

- GKE node pools with GPU limits are less flexible than EKS managed node groups

- Vertex AI has its own serving infrastructure that competes with Ray Serve — there were political conversations about "which serving layer" we should standardize on (enterprise fun times)

- GCS (Google Cloud Storage) has different retry and consistency semantics than S3. Our checkpoint code, written and tested against S3, had subtle bugs on GCS that only manifested under high write concurrency

Part 6: Streaming Responses and Ray Data

Streaming in Enterprise

Token-by-token streaming is essential for LLM serving.

No user wants to wait 3 seconds for a complete response when they could see tokens appearing after 200ms.

At the enterprise environment, we implemented this through Ray Serve with SSE (Server-Sent Events):

@serve.deployment(max_ongoing_requests=50)

class StreamingLLM:

async def __call__(self, request):

prompt = (await request.json())["prompt"]

async for token in self.model.generate_stream(prompt):

yield token

Simple enough.

Except there's a subtle back-pressure problem: if the client is slow to consume tokens, the generator accumulates them in memory.

With 50 concurrent streaming requests, each buffering tokens because the client's network is flaky, you can OOM the actor.

We learned this during a load test when a batch of automated API consumers were making requests but reading responses slowly (they were doing processing between token reads).

Memory grew linearly until the actor died. OOF.

Bounded buffers fix this:

@serve.deployment(max_ongoing_requests=50)

class BoundedStreamingLLM:

async def __call__(self, request):

prompt = (await request.json())["prompt"]

queue = asyncio.Queue(maxsize=100) # Bounded

async def produce():

async for token in self.model.generate_stream(prompt):

await queue.put(token) # Blocks if queue full

await queue.put(None) # Sentinel

asyncio.create_task(produce())

async def consume():

while True:

token = await queue.get()

if token is None:

break

yield token

return consume()

This caps memory usage per request regardless of client behavior.

Ray Data: Training Pipeline

At the fintech platform, we used Ray Data for feeding data into our distributed training jobs.

The key insight: map_batches is NOT map applied to batches. It has fundamentally different semantics.

# map: one row at a time (fine for simple transforms)

ds.map(lambda row: {"text": row["text"].lower()})

# map_batches: processes a numpy/pandas batch (use for GPU work)

def inference_batch(batch: dict[str, np.ndarray]):

inputs = tokenizer(batch["text"].tolist(), return_tensors="pt", padding=True)

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**inputs.to("cuda"))

batch["embeddings"] = outputs.last_hidden_state.cpu().numpy()

return batch

ds.map_batches(

inference_batch,

num_gpus=1,

batch_size=32,

concurrency=4, # Parallel workers

)

The other gotcha: backpressure. If your pipeline has a fast stage (reading from S3) and a slow stage (GPU inference), the fast stage fills memory. You need explicit resource limits:

ctx = ray.data.DataContext.get_current()

ctx.execution_options.resource_limits = ray.data.ExecutionResources(

cpu=16,

gpu=4,

object_store_memory=4 * 1024 * 1024 * 1024, # 4GB cap

)

Without this, we had multiple OOM incidents during our RLHF data preprocessing.

The data loading actor would happily read 50GB of preference data into the object store while the GPU workers were still processing the first 2GB.

(this is a very productive thing to do at 11pm on a friday, highly recommend)

Part 7: The Evolution

Looking across all three environments, there's a clear evolution:

Early days (fintech platform):

├── Ray for distributed training (the hard problem)

├── Everything custom, tight coupling between Ray and compute

├── Small team (~5 engineers), everything is hand-rolled

└── Pain: V100 memory, spot instances, Optuna bugs

Mid-period (enterprise + QSR, simultaneously):

├── Ray for both training AND serving

├── More mature ecosystem (KubeRay, Ray Serve autoscaling)

├── Larger teams, more specialization

├── Pain: enterprise networking, LangChain abstractions, multi-engine routing

Current role:

├── Ray abstracted away by managed services

├── Complexity shifts to application layer (agent orchestration)

├── No GPUs to manage — it's someone else's problem now

└── Pain: different kind — workflow state, tool integration, not GPU orchestration

My deep Ray knowledge is more valuable now than it was at the companies where i was actually using Ray.

Because i understand what managed services abstract away, i can make better decisions about when to use them, when to push back on their limitations, and when a problem actually needs custom infrastructure vs. a managed service.

Understanding Ray deeply means understanding three domains: ML theory, systems engineering, and product requirements.

It sits at their intersection.

The specific APIs matter less over time. The systems thinking endures.

Part 8: Serialization (The Silent Performance Killer)

Serialization overhead is the single most common performance issue i've seen across all three environments, and it's the one the documentation is least helpful about.

Ray uses a dual-path serializer: Arrow for numpy arrays, primitive types, and Arrow-native objects (zero-copy, fast), and Cloudpickle for everything else (slow, memory-hungry).

The performance cliff between these two paths is enormous:

# PATH 1: Arrow-native — near-instant for large arrays

arr = np.random.randn(10_000, 10_000) # ~800MB

ref = ray.put(arr) # Zero-copy into shared memory

# PATH 2: Cloudpickle — orders of magnitude slower

class CustomModel:

def __init__(self):

self.weights = np.random.randn(10_000, 10_000)

self.config = {"lr": 0.001}

model = CustomModel()

ref = ray.put(model)

# Cloudpickle serializes the ENTIRE object graph

# The numpy array gets copied into the pickle stream, THEN into Plasma

# You've now used 3x the memory of the array

At the fintech platform, we had custom model wrappers that looked harmless — small Python classes holding configuration alongside model weights.

Putting them through ray.put() meant the weights took the Cloudpickle path instead of the Arrow path.

Serialization time went from microseconds to seconds. Memory usage tripled. YA ALLAH WHAT IS HAPPENING.

(this one hurt particularly because it looked so innocent in the code)

Store large arrays separately via ray.put() (Arrow path), and only serialize the lightweight metadata:

class LargeModel:

def __init__(self, weights_ref, config):

self.weights_ref = weights_ref # Store the ObjectRef, not the data

self.config = config

def __reduce__(self):

return (LargeModel, (self.weights_ref, self.config))

# Usage

weights_ref = ray.put(weights) # Arrow zero-copy for the big array

model = LargeModel(weights_ref, config)

model_ref = ray.put(model) # Only serializes ref + config (tiny)

This pattern — separate the large data from the metadata, put them through different serialization paths — came up in every environment. At the QSR chain, it was model weights for the inference engines. At the enterprise, it was large embedding batches flowing through the processing pipeline. The same pattern, the same fix, every time.

Part 9: Resource Management Horrors

Logical vs. Physical Resources

Ray resources are logical — they don't map to physical resources unless you make them. num_cpus=1 doesn't pin a process to a core; it decrements a counter. num_gpus=1 sets CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES but doesn't enforce memory isolation.

At the QSR chain, we had two actors on the same node, each declared with num_gpus=1. CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES was set correctly — each saw one GPU. But there's no memory isolation. When one actor's model had a memory-hungry batch, it OOM'd the other actor's GPU. The error appeared in the wrong process's logs.

The num_cpus=0 Disaster

At the enterprise environment, we had coordinator actors — lightweight processes that didn't do compute, just tracked state and dispatched work.

We set num_cpus=0 because they shouldn't consume scheduling resources.

Seems logical, right?

The problem: num_cpus=0 means Ray can schedule an unbounded number of these on a single node, since they cost "nothing" to the scheduler.

Each one is a separate Python process.

We created ~500 coordinator actors. Ray put all of them on one node.

The node ran out of PIDs and memory from process overhead alone. lmao.

Use fractional CPUs:

# DON'T: unbounded scheduling

@ray.remote(num_cpus=0)

class Coordinator:

pass

# DO: soft upper bound via fractional resources

@ray.remote(num_cpus=0.01)

class Coordinator:

pass

# On a 16-CPU node, this limits to ~1600 coordinators

Memory: The Resource Ray Doesn't Track Well

Ray has a memory resource parameter but it's advisory only.

It's used for scheduling decisions but there's no cgroup enforcement. A task that declares memory=2GB can absolutely use 20GB and Ray won't stop it until the Raylet's reactive memory monitor detects the overuse and starts killing workers — by which point you're already in swap hell.

In practice, what i do:

- Set conservative memory declarations (overestimate by 50%)

- Monitor with Prometheus (

ray_node_mem_used) - Build kill-switches into long-running actors that check their own RSS

- Accept that memory management in Ray is a best-effort system and design accordingly

Part 10: Debugging in Production

Log Deduplication Trap

By default, Ray deduplicates identical log lines from workers. 1000 tasks that all print the same error? You see it once. This sounds like a nice quality-of-life feature until:

- You lose the ability to correlate errors with specific tasks

- Intermittent errors that happen 3/1000 times look like they happened 1/1000 times

- All timing information is lost

# In production, ALWAYS disable this

ray.init(

_system_config={"enable_worker_log_dedup": False},

)

Hanging Task Debugging Playbook

The #1 production debugging scenario i've encountered: tasks that never complete.

My playbook:

Check 1: Are you calling ray.get() inside a task?

@ray.remote

def outer():

ref = inner.remote()

return ray.get(ref) # Blocks a worker slot

@ray.remote

def inner():

return 42

# If all worker slots run outer(), no slots are available for inner()

# CLASSIC DEADLOCK

This happened at the fintech platform during our PPO pipeline.

The policy model actor called ray.get() on a reward model result inside a training step. Under load, all worker slots were occupied by policy training, leaving no room for the reward computation.

Deadlock. Training just... stopped. No error, just silence. Fun times.

Use async tasks, or ensure you have more worker slots than your maximum concurrent blocking calls.

Check 2: Placement groups that can never be satisfied

Run ray status. It shows pending placement groups and why they're pending.

Check 3: Object transfers stuck

Run ray memory --stats-only. Look for objects with pending transfers.

Check 4: NCCL timeout

The default NCCL timeout is 30 minutes. A single hung GPU will block all workers for 30 minutes before the error surfaces. Set NCCL_TIMEOUT to something shorter (5-10 minutes) unless you have a good reason not to.

Metrics That Actually Matter

After three deployments, these are the Prometheus metrics I alert on:

ray_object_store_memory — approaching limit = spilling imminent

ray_node_mem_used — approaching physical limit = OOM imminent

ray_gcs_update_resource_usage_time_ms — high = scheduling degradation

ray_serve_num_pending_queries — high = inference saturation

ray_raylet_num_infeasible_scheduling_classes — stuck tasks

The Ray dashboard is fine for development. It is not sufficient for production observability. Export to Prometheus/Grafana and set up real alerts.

Part 11: The Antipattern Hall of Fame

#1: Million Tiny Tasks

# BAD: scheduling overhead dominates (1-5ms per task)

refs = [process.remote(item) for item in million_items]

# GOOD: batch into chunks

refs = [process_batch.remote(chunk) for chunk in chunked(items, 1000)]

Rule of thumb: if your task runs for less than 100ms, batch it.

#2: Passing Large Objects as Arguments

# BAD: serializes big_data for EVERY task call

big_data = load_huge_dataset()

refs = [process.remote(big_data) for _ in range(100)]

# This serializes big_data 100 times!

# GOOD: put it in the object store once

big_data_ref = ray.put(big_data)

refs = [process.remote(big_data_ref) for _ in range(100)]

i hit this one at the enterprise environment with our embedding batches.

The fix took about 30 seconds to implement and cut task submission time by 100x.

(embarrassing in retrospect but extremely satisfying to discover)

#3: Global State in Tasks

# BAD: global state is different in every worker process

counter = 0

@ray.remote

def increment():

global counter

counter += 1 # Each worker has its own copy

return counter # Always returns 1

Use actors for shared state. Always. This isn't a suggestion; it's a fundamental property of Ray's process-per-task model.

#4: Not Handling ObjectLostError

Objects can be lost due to node failure, owner death, or object store eviction. In production, ObjectLostError will happen. Wrap your ray.get() calls and have a recovery strategy.

#5: max_concurrency Defaults for Async Actors

max_concurrency defaults to 1000 for async actors. If your async method allocates significant memory (like, say, loading a batch onto a GPU), you now have 1000x the memory pressure. Always set this explicitly based on your actual capacity.

# ALWAYS explicit

worker = InferenceActor.options(

max_concurrency=8, # Match your GPU batch capacity

num_gpus=1,

).remote()

#6: Detached Actor Leaks

At the enterprise environment, we used detached actors (lifetime="detached") for singleton services — a global rate limiter, a model registry cache, a metrics aggregator.

Detached actors survive driver exit, which is the whole point.

But if your job crashes before cleanup, those actors become orphans consuming resources indefinitely.

We found 47 orphaned detached actors during a cluster audit.

Each was a Python process holding memory and (in some cases) GPU handles. Combined, they were consuming 12GB of RAM and 2 GPU slots on a node that thought it was "fully utilized" but wasn't doing any useful work.

(discovering this was... a moment lol)

An actor reaper pattern helps:

@ray.remote(lifetime="detached", name="actor_reaper", namespace="system")

class ActorReaper:

def __init__(self):

self.registry = {} # name -> (created_at, max_ttl)

def register(self, actor_name, namespace, ttl_seconds=3600):

self.registry[(actor_name, namespace)] = (time.time(), ttl_seconds)

async def reap(self):

while True:

await asyncio.sleep(60)

now = time.time()

for (name, ns), (created, ttl) in list(self.registry.items()):

if now - created > ttl:

try:

actor = ray.get_actor(name, namespace=ns)

ray.kill(actor)

except ValueError:

pass # Already dead

del self.registry[(name, ns)]

Always use explicit namespaces too. The default namespace is "" (empty string). If different jobs use the same actor name in the default namespace, they'll collide silently. We had two different teams' model servers fighting over the actor name "model_server" in the default namespace.

Part 12: Performance Checklist

This is the checklist I run through before every Ray deployment now, born from the accumulated scar tissue of three production environments. I asked Claude to help me organize this for ease of you, the reader, in working with Ray.

Pre-deployment:

/dev/shmsized appropriately (Docker:--shm-size, K8s:emptyDir)- Object spilling configured to fast local storage (NVMe, not EBS)

OMP_NUM_THREADS=1andMKL_NUM_THREADS=1set (prevents CPU oversubscription)- Log dedup disabled

- Prometheus metrics export configured

Scheduling:

- Small tasks (<100ms) batched into larger chunks

- Large objects passed via

ray.put(), not as arguments - Placement groups used for GPU topology requirements

- Fractional CPUs for lightweight actors (never

num_cpus=0)

Memory:

- Object store usage monitored with alerts

- Driver doesn't hold too many ObjectRefs (tree reduction for fan-out)

object_store_memoryset per node- Regular

ray memory --stats-onlychecks

Training:

- Checkpoints go to shared storage (S3/NFS), NEVER local disk

- All workers call

report()(it's a barrier — miss one and everyone hangs) torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark = Truefor fixed input sizes- NCCL env vars set (

NCCL_DEBUG=WARNminimum,NCCL_SOCKET_IFNAMEfor network pinning) - NCCL timeout reduced from default 30min to 5-10min

Serving:

target_ongoing_requests= 50-70% ofmax_ongoing_requestsdownscale_delay_sset conservatively (5+ minutes for GPU workloads)- Health checks in separate concurrency groups

- Async actors for I/O-bound serving

Part 13: What i'd Tell Myself Three Years Ago

If i could go back to the beginning, starting the fintech platform:

1. Ray is infrastructure, not a library. Treat it with the same respect you'd give Kubernetes or PostgreSQL. It has operational characteristics, failure modes, and performance cliffs that you NEED to understand before you go to production.

2. The ownership model is the most important concept. Not tasks, not actors, not Serve. Ownership. Understand who owns what ObjectRef and what happens when that owner dies. (seriously, this one will save you $800 in compute and 18 hours of PPO training)

3. Start with the napkin math. Before writing a single line of Ray code, calculate your GPU memory budget, your serialization overhead, your network latency requirements. These numbers will tell you which placement strategy to use, how many GPUs you need, and whether Ray is even the right tool.

4. Budget time for the environment. Network configuration, shared memory sizing, Docker/K8s setup — this is 30-50% of the actual work in a regulated enterprise. The Ray code itself is maybe 20%. (enterprise environments are a special kind of learning experience)

5. The simpler solution might be better. In my current role, Ray is nowhere in the stack. Managed services handle model serving. The complexity lives in the application layer now — agent orchestration, workflow state management, tool integration. The fact that i deeply understand Ray helps me recognize when i don't need it. That's maybe the most valuable thing it taught me.

Closing

Here's the scale of what these Ray-powered systems touched:

Fintech Enterprise QSR Current

GPU spend 5 figs/mo 5 figs/mo 5 figs/mo ~$0 (managed)

Ray usage Heavy (core) Heavy (core) Heavy (core) None

Scale Internal Thousands Hundreds > Million users

Model size 3-7B 13-70B 13-70B Managed

Ray is the most powerful distributed computing framework i've worked with for ML workloads.

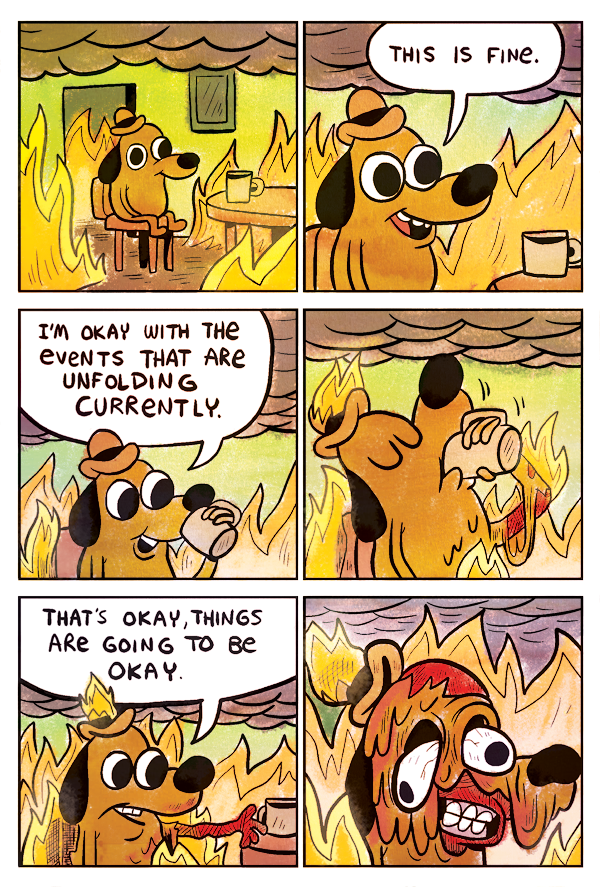

It's also the most footgun-laden.

The difference between "this is amazing" and "why is everything on fire" is understanding that it's infrastructure. It has its own gravity. You orbit around it or you collide with it.

The honest truth: you will lose training runs. You will debug for hours only to find it was /dev/shm. You will watch spot instances die mid-training. You will spend weeks on network approvals.

But once you internalize the patterns — ownership, placement, serialization, resource isolation — Ray becomes the thing that lets you build systems that would be impossibly complex otherwise.

The engineers who succeed with Ray are the ones who stop trying to use it and start living with it.

If you're in the middle of a production deployment right now and something's broken: you're not alone. These patterns are hard-won. Take the checklist. Use the playbook. And when you find a new footgun, write it down.

That's how the next engineer learns.